- Insights

- Slideshow

The Water Guardians of the Andes

At first glance, there is little in common between the village farmer herding his cattle in the pastures of the Peruvian Andes and the office worker toiling at his desk in the capital city of Lima. But they both depend on exactly the same water source. There are few more powerful examples of the interconnectedness of ecosystem health and human wellbeing.

The Water Guardians of the Andes

Lima is located in a narrow trip of coastal desert squeezed between the Pacific Ocean and the Andean cordillera. It is one of the driest places in the world, yet it is the country’s economic backbone. Lima is home to almost one third of Peru’s population and it dominates national industrial production and consumer spending. Up and down the coast, vast stretches of irrigated agricultural land that produce all-year-round asparagus, avocados, berries, and other high-value crops that are exported to the supermarkets of Europe and America.

The water needed for all this activity is abundant because of the adjacent mountain range, which functions as a natural water tower. When air masses from the Pacific hit the Andes, they are uplifted and generate rainfall. Together with spillover rainfall from the wet Amazon basin, this moisture feeds the rivers that run off to the coastal plains, where they provide water for the city and the agricultural irrigation systems. But there is a major problem with this supply: it is overabundant in the winter and spring, but it dries up to a trickle in the dry season of summer and fall.

The Water Guardians of the Andes

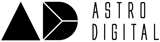

Up in the humid highlands, smallholder farmers make a living from cattle grazing and growing crops such as potatoes and beans. They use water from the hundreds of small streams that eventually feed into the major rivers supplying the coastal desert. But, in using this water, they also need to safeguard downstream water supplies. On the steep slopes of the Andes, soils are very prone to degradation and erosion. Compacted and damaged soil cannot absorb and store water very well, leading

to higher rates of runoff and high peak flows laden with sediment that clogs downstream irrigation reservoirs and canals. To avoid this, farmers need to to be active in reforesting slopes, protecting wetlands, and adopting soil conservation strategies. Their challenge is to find a precarious balance between generating sufficient income for themselves, while protecting the downstream water resources.

The Water Guardians of the Andes

The community of Huamantanga is a perfect example. Its farmers own numerous cattle that graze in a part of the basin that provides water to Lima. Recognizing the need to improve land and water management, the community joined forces with a local development NGO, CONDESAN, to get a better grasp of the impact of cattle grazing on streamflow.

The Water Guardians of the Andes

The farmers and CONDESAN installed hydrological monitoring equipment in two mountain streams descending from the grazing lands. Then, they closed off one watershed to all cattle.

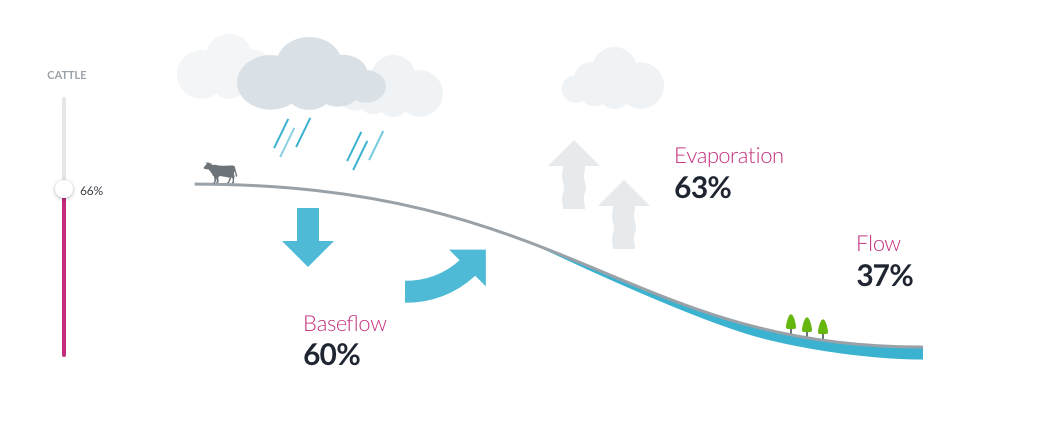

With the scientific support of an international research group, they were able to look at different scenarios, to help find the ideal balance between cattle grazing and streamflow.

The Water Guardians of the Andes

There is another, fascinating, way to enhance streamflow during the dry season. Centuries ago, Pre-Inca civilizations dug small canals that diverted water from the gushing upland streams in winter and allowed it to “leak” into the soil. Weeks, or even months, later, the water would emerge as much as a kilometre downslope, where it feeds small wells that can be used for summer irrigation.

In Huamantanga, some of these old canals still exist. The ancient technique is locally called “mamanteo” (breastfeeding in Spanish) but it had fallen into disuse over the years, as many farmers moved to the city.

The Water Guardians of the Andes

With scientific support to quantify the potential impact of mamanteo, the community decided to refurbish some of the old canals. CONDESAN, added small quantities of dye to water in the canals, to track its movement and quantify the travel time of

water down the hillslope. These data were combined with a hydrological model to assess the potential for increasing streamflow during the dry season.

The Water Guardians of the Andes

The ancient mamanteo system could serve as a complement or even a potential alternative to building expensive and fragile water reservoirs or desalination plants. Lima’s water utility, Sedapal, has recently decided to invest up to $23 million in “green infrastructure” such as reviving the old canals. The utility believes that mamanteo might lead to a substantial reduction in the city’s water deficit during the dry summer months.

Credits

- Consortium for the Sustainable Development of the Andean Ecoregion (CONDESAN)

- Forest Trends

- The Nature Conservancy